Edition 1 (2014), Viborg Kunsthal, Viborg, Denmark

Exhibition: Time as Matter / Materialisert tid, Jan Christensen & Marius Dahl

October 31 2014 - January 11, 2015

Head of Exhibitions, Viborg Kunsthal: Helene Nyborg Bay

Editor: Power Ekroth

Interview: Power Ekroth

Design and layout: Jan Christensen

Copy editor: Bodil Johanne Monrad

Cover photo: Jan Christensen & Marius Dahl (3D model and rendered image)

Photos: The artist unless otherwise indicated

Printed by Speciatrykkeriet Viborg A/S, Viborg

400 copies

Typeface: Akzidenz-Grotesk BQ Paper: Arctic Silk + (130 g.),

Carta Integra FSC (235 g.), 96 pages

Scribus 1.4.3 Open Source Desktop Publishing

ISBN 987-87-90192-86-0 Viborg Kunsthals Forlag 2014

Viborg Kunsthal

Riddergade 8 DK-8800 Viborg

Denmark

Tel +45 8787 3220

viborgkunsthal@viborg.dk

www.viborgkunsthal.dk

This edition was produced with generous support from OCA, Oslo, Norway

Viborg Kunsthal, Viborg, Denmark, 2014

NOTHING IS FOR FREE, MOTHERFUCKER$

By Power Ekroth

Power Ekroth: Jan, would you care to tell me why you decided to become an artist?

Jan Christensen: I was seeking an independent lifestyle from very early on. My parents had lived abroad in New York and Copenhagen (where I was born). They trusted me with responsibilities from an early age. They were not involved in art themselves and I was not exposed to art in particular, but they always encouraged creative thinking and I remember finding interesting articles on art in books and papers. We had intelligent conversations at the dinner table and I read scientific magazines, daily papers and publications such as the Time Magazine regularly. By the time I finished high-school in Oslo, I was critical to the process and demands of the mainstream educational institutions and was seeking a different life. Ultimately, art school was really one of the few options that seemed interesting.

Already in high-school I participated in the early computer scene of the Atari ST-community from around 1988 and in the graffiti scene in Oslo 1991-1994. Both of these interests were of course non-supervised activities that were only instigated by people in the community itself. I got to know several people then who were a little bit older than me and considering how young I was in these years, age 11-17, I must have been influenced and inspired by seeing what my friends achieved either as computer artists, programmers and graffiti artists.

The involvement in the graffiti-scene was halted after I was arrested in a couple of incidents in 1993-1994 and later prosecuted for vandalism in 1995, which only further triggered my critical attitude towards the conformity of general education, public opinion and the mass-media. Considering my run-ins with the law at such a young age, seeing other writers being treated the same way and experiencing what I still consider unfair and biased treatment in court, I had a dark and pessimistic view on society and probably a different idea about the future than many of my peer students.

Power Ekroth: You mention that you were critical of the educational institutions but nevertheless list art school as an alternative which seems to me a bit of an oxymoron. Why were you so critical? Was art school the solution?

Jan Christensen: It’s a difficult question. Perhaps I felt some lack of fundamental productive encourage-ment. Further studies only seemed to bring you to the next level of more studying, for the purpose of keeping as many options open as possible for some unforeseen future. Eventually you would come to some point where you would have to make a final choice of career and living.

At the end of the day, art school definitely put myself in control of my own future, by meeting so many other like-minded young artists, to the point that I felt inspired and empowered to leave art school after only completing a BA.

I think part of this very focused mindset originated with my interest in graffiti practice and appreciating the do-it-yourself attitude of the graffiti writers that I admired. Also, keep in mind that I was arrested when I was 16, but only prosecuted by the time I was 18. It probably affected my ideas of the future at that time. When I entered military service five years later at twenty-three, I was told that I would not have the security approval to apply for the more interesting areas of education there because of my background. Eventually, I left by refusing arms training, and was committed to 16 months of public service, which I luckily found at the newly founded OSL Kunsthall which was initiated by Jonas Ekeberg. I was back in the art scene. By then I had studied in Oslo and already lived half a year in Berlin working for Atle Gerhardsen. Serving public service duty at OSL Kunsthall was the perfect job for me. It was a great time.

Looking back at the work I did as a graffiti artist I would say that my memories of those days and the graffiti that I did, are much better than the photos I have kept. But it was the best time ever – truly exciting times. I still follow the graffiti scene pretty well, and admire a lot of great graffiti artists who create unique designs and put up work in spectacular places.

In some ways that work introduced me to large-scale art productions even before I knew that I’d be pursuing art. Upon leaving art school I decided to skip the whole idea of setting up a studio. Instead I decided I would only work with sketches and proposals, submitting designs for very large wall paintings and whatever other projects I came up with. Eventually that approach seemed to work and I started getting some group shows, public commissions and solo exhibitions without the need to sit around in a studio and only ponder about the work.

Power Ekroth: What were your main inspirations when you started as an artist? How did the inspirational stuff change over the years, and what makes you tick today?

Jan Christensen: As I did not get into art school right away after high-school, I spent a full year working in a bookstore and night-shifts at a couple of 7-Elevens, while I read art books that I found interesting and painted oil paintings, mainly based on my own photographs or copies of art works I'd come across. I'd basically paint whatever I liked, with the idea that I might have some tiny kind of insight into the process of making an historical artwork by re-creating it. I studied the works of the Dutch genre-painter Jan Vermeer and copied several of his works in detail. That was a bridge to painting based on photographs, inspired by artists such as Chuck Close, Richard Estes and Robert Bechtle, realizing that it wasn't necessarily the specific motives that were important to such work, but mimicking the photographic effects of the lens and understanding the effects of light as it hits the different materials, which was basically the essence of Vermeer’s aesthetic practice as well. At the same time I brought with me a refined sense of illustration and drawing, particularly inspired by artists such as Horst Janssen and Egon Schiele. Already while in high-school I met Anders Nordby. We would do a lot of drawing and hung out discussing art and visited exhibitions in Oslo. We would go do sessions of croquis drawing every week. He would eventually study design before our paths ultimately crossed again when he entered art school ten years later. He’s a really dedicated personality, though an unusual kind of artist, who keeps his head low and likes to keep out of the spotlight. Our mutual experiences and discussions were definitely crucial to my own early development in the mid-nineties.

For a long time I think other artists and specific artworks, including historical art, inspired me in the sense that I wanted to learn a lot more and found ways to analyze and study by paraphrasing and referring to art history and discourse. In general, I guess my time as a student was all about this. I remember never participating in any group shows or anything as a student – I was not interested in displaying anything at all. I just focused on studying, reading and constantly discussing things with my fellow students and hanging out.

I saw a lot of art, I really saw every show that was put up in Oslo, from posters in frame shops to the permanent collections on display at the National Gallery. I’d make a project out of mapping and scrutinizing the exhibition spaces in Oslo, already as a student. This almost scientific approach to learning also includes my curatorial research practice. As a curator I find it interesting to meet new artists and help them realize new work, or give others another chance to show some old work that might have been wrapped up and forgotten. There is so much work out there that just needs the right context or new angle of appreciation.

Now, fifteen years later, I still push through projects that require learning new skills, working with more and more professional teams from diverse fields of production. These days, I think a lot of the current inspiration actually comes from looking at the materials at hand and working with the limitations at the site, which might be practical challenges as well as conceptual considerations. There will always be limitations to the financial budget of a show. My process of working involves constant archiving of ideas and looking back at former projects – including those that were never realized – and bringing some of those ideas back out. This way there’s a constant reconsideration of ideas and development going on. And I think that the earlier approach, the way I’d make more obvious references and such, is more hidden or veiled today. As certain aspects of art-making is more of a routine, you might think it would be easier to convey the details of the process, but I feel like everything is somehow internalized and less conscious now.

Power Ekroth: Did you ever consider making photographic works instead of painting, or even experimenting with the photographic medium, considering you were interested in representation – and painting?

Jan Christensen: Photography has always been a fascination, but it took a while before I seriously considered doing any photographic work. I did acquire a digital camera back in 1998 or something, while I was in art school, but I only used it to document the progress of my projects and such. Keep in mind that was the day of one or two mega pixel cameras. Over these years, it has been interesting how digital photography has empowered everyone to express themselves creatively beyond what other kinds of tools have done. Of course that has complicated the discussion of art and photography, pushing the bar even higher, when it comes to creating that meaningful image. To me, we have seen some of the most innovative and yet different artistic strategies of our time in this field, with the two German artists Wolfgang Tillmans and Thomas Demand. Whenever I use the photographic medium, I use it to visualize or render some specific idea or as an integrated technique within a larger project. I don't yet produce series of photographic artworks per se.

Power Ekroth: What is your connection to ceramics?

Jan Christensen: I entered the department of ceramic art at SHKS (KHIO) in 1997, that's how I got involved there. I didn’t keep much of my ceramic work from back then.

I guess I considered it to be educational experiments, as well as everything else I would do. I’d be making motives of simplified architectural details in oil or acrylic paint. I drew a lot of self-portraits for exercise, inspired by the before mentioned Janssen and Schiele, as well as Lucien Freud’s work.

My ceramic work concluded in a very interesting project in different stages: I would produce a mould of a found plastic container, transform or modify several reproductions from that cast and re-combine these shapes. This method would be repeated within the same sequence which created some weird hybrid shape that still kept certain details from the original plastic container. The very last stage of production would be completed in porcelain, bronze or compact silicone or something like that, which would be the object on display. The project also included some fairly detailed drawings and descriptions of every stage of production, which would be required to accompany the sculpture, like a certificate of authenticity. I think those works were very much inspired by such different artists as Richard Deacon, Donald Judd and Allan McCollum, dealing with abstraction, material and technical complexity and seriality. I was also reading a lot about Conceptual Art and Minimalism in general at that point.

Power Ekroth: Why did you move to Berlin?

Jan Christensen: I worked for Atle Gerhardsen at his gallery in Oslo. When he was relocating to Berlin in 2000, he offered me to come along, until I would have to return to Norway for the upcoming military/ public service, that I knew would happen later. So I came to Berlin with his gallery and got to meet all his friends there right away. I remember being shown around Kreuzberg the very first night by Dominic Eichler (former art critic with Frieze and other magazines; future gallerist of Silberkuppe) who handed me the key to my flat, which was some flat that was registered on Olafur Eliasson so that any parking tickets – there were quite some – would get lost. The second night or something, I was invited to a dinner at Edd’s (legendary Thai restaurant and hang-out for the art crowd in the 90’s), with Atle Gerhardsen and a gang of people from neugerriemschneider, chatting with Simon Starling, who was an artist I already appreciated and admired. This is just to illustrate how social and mesmerizing the scene in Berlin was just then.

I also met Rirkrit Tiravanija early on in Berlin. I was assisting him on some projects in Oslo (2001-2002) and I helped out on a project in Wiesbaden (2002). Being able to see how he worked and understanding his approach to the artworld and the obstacles involved in creating his projects, has probably been much more instrumental to my practice than most people will ever understand.

He had a pragmatic and efficient attitude towards the world and a lot of positive energy and an open mind with regards to his collaborators and colleagues. It’s interesting how you only later realize how people affect your art, and Tiravanija is someone who really has inspired me. You probably wouldn’t be able to tell from analyzing a single piece of work, but when it comes to the overall production and general attitude, I would say he probably inspired me to constantly explore my interests and keep evolving as artist.

Power Ekroth: Speaking of inspirations, I remember a work in Stockholm, at Galerie Nordenhake actually, that took its point of departure in a work by Jonathan Monk.

Jan Christensen: Jonathan Monk lives in Berlin. He was also there from early on, together with another very interesting conceptual artist, Isabel Heimerdinger. He was around and caught all the shows, you’d see him everywhere. He is such a dedicated artist. The show I did at Nordenhake in Stockholm in 2003 paraphrased his work (simply referring to his original title, You’re Always Alone in the Cinema; using imagery that included some photos of Monk and his family), thus making it somewhat of a total meta-work, considering that so much of his work is paraphrasing art. Still, it kept some of the melancholy of life, which a lot of his work holds. I have curated a couple of shows with his works as well, which were very well-received exhibitions (Perfect Timeless Repetition, c/o - Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin, 2003 and Ten Raised to the Eighy-first Power, Galleri MGM, Oslo, 2008).

Power Ekroth: The social scene of Berlin and Oslo – are there any differences? And how much has this art-socializing in different cities affected your work?

Jan Christensen: My life is essentially actually quite a lonely and partly introvert situation, at times traveling extensively and also keeping apartments in both Berlin and Oslo, though I hear people say I’m always around or that I’ve introduced people, generated opportunities for others and such. I’ve done multiple residencies throughout my career, which of course affected both professional and personal relationships.

But yes, I also do work extensively in teams, like a project that included the scenography for a theatre play and especially the many projects with Marius Dahl. I have collaborated with several different people, but I guess the projects with Marius Dahl represent a pretty unique and very fruitful collaboration. To be honest, I am not sure how the different scenes of Berlin and Oslo have affected my work. There has really been a lot of different people passing through, a lot of friendships and interesting meetings. But I think it has been very interesting to be able to see these different places develop over the last fifteen years and at the same time see how different artists and their careers have changed over time. There are certain artists and friends in Berlin who have been particularly close at certain times, such as Jordan Wolfson, Matthew Antezzo, Lina Kunimoto, Lars Morell, Bjørn-Kowalski Hansen, Halina Kliem, Marcel Dickhage and Mario Gamper. For example, the latter, Mario Gamper, is a guy with a background in advertising, working for large commercial campaigns and overall strategies. He’s been a very interesting conversation partner and provided great insights in the world of marketing, new media and so on. I remember when I was an artist in residence at Montana State University in 2010, courtesy of Rollin Beamish, running a huge workshop with students across several departments, re-enacting Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Mario passed through the state of Montana to conduct a couple of stunning lectures to the design students on a whim. These kinds of friendships and collaborations are what I can appreciate, providing unexpected views on things. And in general I have to say going to Montana was a blast for so many reasons. I still expect to see some of those students explode onto the art scene.

Power Ekroth: You have been doing loads and loads of traveling over the years. Many of those trips have been to Korea where you also held a residency at one point. You have also been to residencies in many other places, but I can only remember Ireland and Stockholm now. This “residency-hopping” is something very special for artists in our time. How has this affected your friendships and your work?

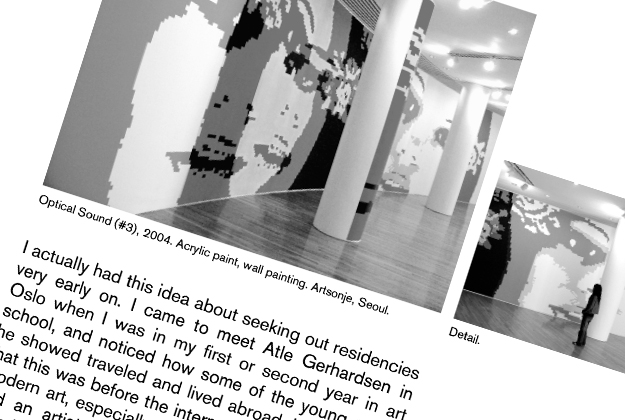

Jan Christensen: I actually held two proper residencies in Seoul, in 2004 at the International Studio Program of Changdong, The National Art Studio in Seoul and in 2012 at Seoul Art Space Geumcheon (SASG). And I have been very fortunate to work with people in South-Korea who have invited me back for other projects and collaborations, like Sunjung Kim, Jooyoung Lee, Jiyoon Lee. South-Korea has been a very exciting and different place to work and live.

I actually had this idea about seeking out residencies very early on. I came to meet Atle Gerhardsen in Oslo when I was in my first or second year in art school, and noticed how some of the young artists he showed traveled and lived abroad. Keep in mind that this was before the internet really covered much modern art, especially any current contemporary art, and an artist basically had to meet curators and gallerists and journalists in person or work with dedicated gallerists and dealers. Residencies were places where such encounters happen naturally. You can basically cross-check the exhibitions and residencies of any artist’s CV and backtrack his or her career to a couple of few important such moments. Of course, these days, a lot of people maintain some kind of online exposure, but I still believe that it’s crucial to meet in person, see different art scenes and travel the world to understand where you belong and eventually settle down and accept and appreciate whatever scene your work fits in. There is a whole lot of trial and error, messed up love stories, professional encounters and wonderful, fun moments that you probably would not have thought you’d ever see, but which help you step it up a little further, or make you realize what you have to sacrifice to do so. Sitting around in one place only, in the place where you once studied and have all your friends, is not necessarily going to make you a very successful artist outside that small circle of insiders.

I’ve experienced repeatedly the need to re-start my head and explain myself from scratch when I relocated to another city where I didn’t know anyone. It’s a very good thing. And it also contributes to new ideas and opens up to new collaborations. It clears your head pretty well. I probably did different kinds of residencies annually between 2002-2012. Some were short stints while some lasted longer. Sometimes, when I had very little money, the grant included with the stay, provided the only money I had. But yes, it’s definitely not something that suits everyone. These days I’m too busy working on projects and have decided to strictly limit my time, no longer seeking (many) residencies. The constant moving also used to mean that I saw family, friends and colleagues more rarely. Some relationships really suffered.

I have a great place in Berlin, which is the place I am most comfortable working, but I am just as close to the art scene in Oslo and involved in projects and institutions there, and thus spend a lot of time in Norway as well.

I know Seoul very well from my several long stays and love the culture and cuisine, it’s definitely a place I could imagine living again. When I did a residency at SIM in Reykjavik in 2010 I was surprised how nice it was and imagined how I could completely retreat to Iceland. But artwise, I guess mainland Europe is somehow pretty important, thus staying in Berlin makes sense. It’s still baffling to me how the Nordic countries are perceived by professionals internationally, who really consider it the outskirts of the art discourse and geographically periphery. The travels I did for projects and residencies brought me to places I would not have visited otherwise.

Power Ekroth: I would like you to elaborate on your work with Marius Dahl. How did that come to life, and how does it work to work together? I know you have been working together with mostly public commissions, and all by yourself you have also been commissioned to do a lot of different public work.

Jan Christensen: I met Marius Dahl at SHKS (KHIO) in Oslo where we both studied at department of ceramics. He was about to finish his MA when I started in 1997. He soon moved to Istanbul with his wife and children and lived there until around 2012, when they returned to Norway.

He got back in touch around 2011 with some ideas for projects and we started working on proposals and entered some competitions. Some of these early collaborations were unsuccessful. But because we were based in different countries, we set up a pretty complex structure of management, tools and software such as Skype and Dropbox, that enabled us to quickly communicate and work on projects in a very efficient way. We soon got to see some of our ideas realized, winning several competitions for public art projects. Our combined knowledge and interests have proven quite successful. Marius is an extremely ambitious artist with an ability to pick up new skills very quickly. A lot of artists seem to be happy where they are, literally painting the same canvas their whole lives. Marius completely shares my curiosity for technology and different media, always pushing ahead.

He’s got more technical knowledge and an overview of materials than me, while I’ve partly introduced him to 3D modelling, CAD and rendering software. Such tools enable us to produce work on a very different scale and complexity than you would be able to do in a normal studio situation.

Power Ekroth: Speaking of public works, I think about the monumental work you exhibited on the facade of the Oslo Central Station in 2011 named A Melancholia. Knowing a bit about the background for it, I know this was a very difficult work to exhibit in a difficult time.

Jan Christensen: The artwork in question, A Melancholia, was a large three-part public project at the central train station (Oslo S) in Oslo, produced only two months after the events of July 22, 2011, when a bomb devastated the government complex downtown Oslo, killing 8 people, and the murders of 69 people at Utøya outside of Oslo on the very same day.

I had originally been commissioned to produce a temporary large-scale work for the train station. As the events of that day unfolded, I immediately questioned putting up some public art work in Oslo without reflecting the shocking facts of recent time, which also seemed very difficult to ever do. But I had very good conversations with many people, as well as the curator, Vibeke Christensen, and she really encouraged me and trusted that I could turn this doubt into some kind of artwork that would prove important at that time.

It was a very challenging piece, which consisted of two large photo prints and multiple looped video sequences of the sun as it bursts and flares through different landscapes, partly blinding you, inside the train station. It was interesting to produce a work that really had to reflect a traumatic recent moment that really affected the entire society and general public discourse.

Power Ekroth: Looking back at your diverse, and large, art production I can see you have made a lot of twists and turns. Many artists I know, who had a taste of success in their early years tend to sort of “stagnate” (for the lack of a better word) due to several things, like for instance the demand of the market/curators/dealers to live up to their previous work and tend to repeat themselves. For some, it is also driven by the fear of failing. This description does absolutely not apply to you. Sometimes I even have difficulties to find the common denominator in your work since things look really different over time. Can you see this yourself? If so, can you describe it?

Jan Christensen: I think I had an understanding of the commercial art market very soon, before I even entered the scene as an artist. I had some thoughts on how to make my effort last a little longer – that is if I’d ever have any impact at all. And part of the strategy was to be an artist that is first and foremost respected by other artists.

The art marked really doesn’t matter if you don’t have the support of the core art scene and the other participants there, which include critics and curators as well. Keeping a diverse production would also help avoid getting categorized and placed within a certain movement, which would not benefit my idea of an independent practice. Sure, I did a lot of wall paintings for example, but they were not even necessarily aesthetically or conceptually coherent. I guess I have a curious mind in general, and I seem to route my interests into the art practice somehow.

Power Ekroth: What do you see yourself doing in ten years?

Jan Christensen: I hope to be involved in more large-scale art projects, possibly more architectural and complex public sculpture. Hopefully, my interests and practice have kept evolving. I don't see a reason to play anything safe and necessarily halt this process of constant learning and experimenting, which I consider fundamental and inherently interrelated to art production. I have been conscious and strategic when it comes to taking on opportunities such as lecturing, teaching and committee work, curating and assisting several institutions. Rather than asking myself what I’ll be up to, I’d say I am quite curious what my fellow colleagues are doing; all those people I’ve met throughout the years in Oslo, Berlin and traveling elsewhere. The fact of the matter is that your career doesn’t just develop on its own, though it might feel or seem that way when the artist is looking at it from her or his single perspective only. It actually develops in sync with the careers and discourse of your friends and general network. This is why the social scene is such an important place, even if it might not seem to go anywhere a the moment – it might even seem like a complete standstill for years, until someone suddenly shoots out or makes something very unique or special, even better, perhaps something iconic to a generation of artists, and suddenly pulls along everyone that happens to hang around.

Power Ekroth: So, what about the concept of time in your work? And how do you see your own development over time? Often, when one is at the beginning of one's career, time can feel like it comes unlimited, but after having worked for a decade or so, something changes in how one perceives time. Also, knowing you for a long time, I know that you almost never stop working. Do you even have a concept of “free-time”? I often think about Bergson’s theory of time, both that he thought it impossible to plan for the future since time itself unravels unforeseen possibilities and also that time is not something you can divide into smaller entities, instead, time is a flowing thing that is also dependent on how we perceive time. Time is different when we wait for something (it “feels” slower) than when we are having fun, sort of.

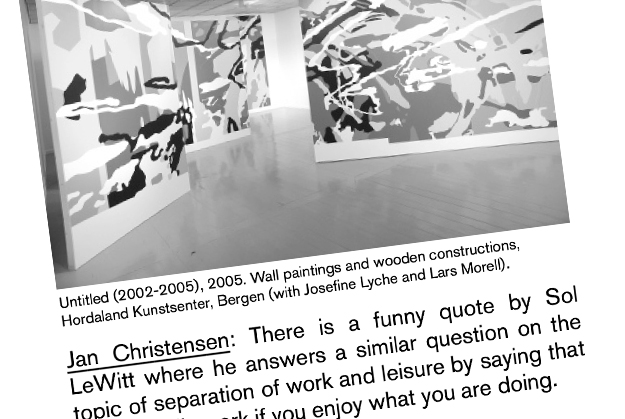

Jan Christensen: There is a funny quote by Sol LeWitt where he answers a similar question on the topic of separation of work and leisure by saying that it's not really work if you enjoy what you are doing.

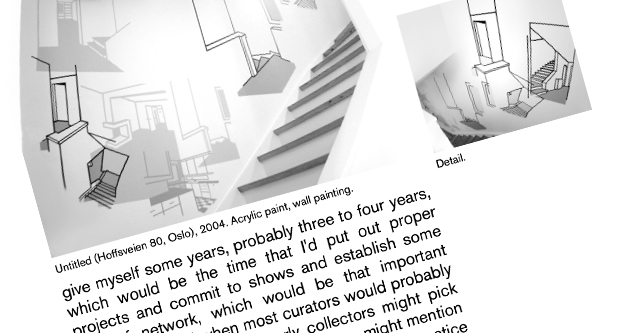

I felt I had lack of time when I went to high-school, when I felt an urge to make something of myself. Later, art school felt increasingly irrelevant by the third year (sixth term/BA), while everyone I studied with would complete the full nine terms. Meanwhile, I was fully aware that the process of getting shows and being eligible to apply to grants and residencies, would be years ahead. Entering the art world is much like re-starting everything, thus spending too long in art school is not necessarily benefiting to your progress. I was worried that I'd miss out on the limited period of transition from art school to being a young and upcoming artist, which is the period when most people are curious about your work, but nobody really knows what it's all about yet. You might not even have a clear idea about the full scope and ambitions of your work yourself. That time is crucial, because if something you make is interesting, somebody might give you a couple of great opportunities. I think I even thought up a strategy about that while I was in art school and used that time for experimentation only. Upon leaving school I'd give myself some years, probably three to four years, which would be the time that I'd put out proper projects and commit to shows and establish some kind of network, which would be that important transition period when most curators would probably pay attention and some early collectors might pick up some work. Eventually some critics might mention the work and help contextualize my general practice and perhaps some gallerists, collectors and independent curators might notice.

I was aware that this would not happen completely on it's own, thus I would depend on the general discourse at that moment. Not saying that I necessarily caught on to what was going on aesthetically, but I was consciously positioning my work within certain contexts and was careful to limit my exposure to other contexts and situations. For example, I knew how some dealers claim how an artist needs to establish a dealership before the age of thirty if you would ever have a chance of experiencing success, but I was still in my early twenties and did not feel the need and hurry to necessarily make a lot of sales immediately. Essentially, conceptual art is my field within the whole practice of the arts, and I knew well how that kind of practice develops slowly, sometimes completely escaping the general market. So there was a mix of urgency and stress to get started working on my main project while I knew I had some time to establish myself properly. In Oslo there were artists like Vibeke Tandberg and Børre Sæthre who really inspired me. I had the chance to experience a tiny little bit of her tremendous international success through working with her as an assistant at Atle Gerhardsen's gallery. Børre Sæthre included Marianne Zamecznik and some of us others in his work crew on certain shows. His installations are legendary and were important moments in Norwegian art history; he combined the ambitious scale – on the verge of architecture, such as Jorge Pardo and Andrea Zittel – with a personal, intimate world, similar to Felix Gonzalez-Torres.

As a student I remember being able to have chats about art with Torbjørn Rødland. Jeannette Christensen and Annika Ström were other artists that I could relate to that I met through Atle Gerhardsen. The theoritician Åsmund Thorkildsen conducted extremely clever lectures on recent art history in art school. During my few years there were studies of abstract expressionism, minimalism, conceptual art and a lot of contemporary art. He was highly influential to a few of us (Marianne Zamecznik, Øystein Aasan, Halvor Haugen and some others), though completely lost on many of the other art students back then.

Power Ekroth: I’d like to ask you about the use of space in your work. There are quite a few examples where your work are two-dimensional, and of course the wall-paintings can indeed be considered to be two-dimensional in one aspect, but many of these make use of the space the works are installed in for instance. There are other examples where the works are transported into the ceilings or floors too.

Then there are your audio works, and sculptural installations, not to mention the public art works which many are made in collaborations with others, and many of which in nature are sculptural and hence spatial. Also, several installations from the past are to be explored by the visitor, you have to walk around in the installation in order to experience them. Would you like to mention some of the things from the different categories that you feel are either really successful (in your own mind) and mention your intentions briefly?

Jan Christensen: Perhaps the most specific answer to the question of my interaction with space and how I think about this artistically, it is that I am pretty confident and bold when it comes to challenging any kind of surface and occupying space with my installations. I have a certain way of organizing or placing things out of order, non-aligned and out-of-center. I also believe that certain things do work the best when it’s placed by accident or by some random order. At the same time I am an avid model constructor, but I mainly use the architectural model or the mockup of the artwork to get the feel of the space in different dimensions, which helps me feel even more confident when I have to manage the real situation.

The different concepts that I’ve applied to different projects have mostly been conceived as different series of works. But for example, when it comes to the wall paintings, sometimes even those ideas got mashed up and ended up in collage-like compositions. I realize that there certainly is a reoccurring aesthetic. Very often I’m satisfied by the first installment of a series, or the prototype, and move on, until I re-visit old concepts and ideas years later.

Sometimes I might have had some ideas, but I wouldn’t be able to execute them until I meet the right person. That was the situation when I accidentally bumped into Anders Fjøsne when I was researching the possibility of setting up a punk band called the NOTHING IS FOR FREE, MOTHERFUCKER$, which would have been a band where the only instruments allowed would have been Tibetan singing bowls, Chinese chimes and so on. Fjøsne happened to be a young musician who worked as an electrician and had the knowledge of assembling his own circuit boards. Together we would design and produce several interactive light- and sound installations over the course of a couple of years.

The large public art projects that I have accomplished with Marius Dahl also share that same attributes: I might have been able to enter some of the competitions or I might have been invited to a project on my own, but I would never have been able to complete so many large projects and at that level of detail unless it was through our joint efforts. He is also experienced in sculpture and model-making, and shares my interest in art that is on the verge of becoming architecture.

Power Ekroth: I’ve had conversations with others that have expressed a frustration over your work since it is difficult to understand how everything you do is related since the final expressions are so different and seem not to be talking about the same things. I can see this as an enormous strength – not to be able to be categorized – however I also see how this can be interpreted as a bit… evasive, for the lack of a better word at the moment. Will the real Jan Christensen please stand up?

Jan Christensen: There are certain aspects of this that I have been conscious about and which I’ve treated carefully exactly for the reason that I consider it interesting to prove independence and integrity. It’s no secret that this kind of attitude actually helps in certain ways when it comes to arguing for financial support or residencies, where they appreciate research and development. At the same time there are the galleries and the art market, which do not necessarily acknowledge these things.

I could definitely have worked harder to appease or satisfy the art market only, but if you consider an artist such as Charles Ray, I’d say most professionals and audience agree that his limited production and unique works of art stand out in the long run. That kind of dedication to the work and commitment to the art discourse is something that I can appreciate. Being able to live and work independently, with a fleeting mind, is what I could imagine the ultimate goal of contemporary art practice.

Power Ekroth is an independent curator, critic and editor based in Berlin.

Jan Christensen (Copenhagen, 1977) lives and works in Berlin and Oslo.

Viborg Kunsthals Forlag 2014 ISBN 987-87-90192-86-0